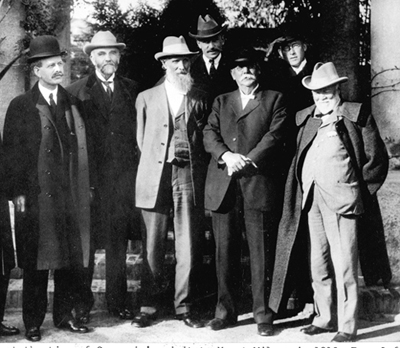

Photo: Andrew Carnegie's visit to Mt. Wilson Observatory in 1910. From left: George Ellery Hale, J. H. McBride, John Muir, H. F. Osborn, John Daggett Hooker, J. A. B. Scherer, and Andrew Carnegie. Photo from the Hale Observatories, courtesy of the American Institute of Physics Emilio Segre Visual Archives.

Hardware millionaire, early West Adams social leader, amateur scientist and astronomer, and donor of the Hooker 100 inch telescope at Mt. Wilson, the largest telescope in the world when it was built.

Hardware millionaire, early West Adams social leader, amateur scientist and astronomer, and donor of the Hooker 100 inch telescope at Mt. Wilson, the largest telescope in the world when it was built.

John Hooker (1838-1911) and his wife Katharine Putnam Hooker (1849-1935) (see entry) were important figures in the early days of West Adams society, between 1886 and 1911. John, born in Hinsdale, New Hampshire, was a hardware and steel-pipe millionaire. John went to California in 1861, living first in San Francisco. In 1869 he married Katharine Putnam of San Francisco. They had two children, both born in San Francisco, Marian, in 1875, and Lawrence, in 1878. Sometime after that they moved to Los Angeles.

In 1886 the Hookers built a large house at 325 West Adams Street (in the nineteenth century it was "street"; we do not know when the name was changed to boulevard). The house, located just west of Grand Avenue on what later became the grounds of the Orthopedic Hospital, included extensive formal gardens and its own stable.

John D. Hooker made his principal fortune in the hardware and iron-pipe business. He was vice-president of the Baker Iron Works, the company that built the first locomotive constructed in Los Angeles, and president of the Western Union Oil Company. He was also an avid amateur astronomer and inventor and a founder of the California Academy of Sciences.

In February 1904 Hooker was approached by George Ellery Hale (1868-1938), the country's foremost scientist and astronomer, who turned down an offer to head the Smithsonian Institute in order to build observatories in the far west. Hale was invited to the West Adams house, where, despite a large difference in age, he began a strong friendship with John and, particularly, Katharine Hooker.

Helen Wright in her biography of Hale writes of his first visit to the Hooker home, "On his arrival he found a large yellow house, surrounded by elaborate grounds. He was ushered into a large living room, its floors adorned with magnificent Persian rugs. Here he was greeted by Hooker, who then led him on a tour of the house and grounds, of which he was inordinately proud. In the stable behind the house he kept two fabulous trotters; in the garden, which was surrounded by a high spite fence [i.e., a fence erected to annoy neighbors] that he had built to keep out the eyes of inquisitive neighbors, he had a fantastic collection of roses that ran to thousands of varieties. He also kept his telescope in this garden." ("Explorer of the Universe: A Biography of George Ellery Hale," p. 181.)

Hale had founded the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory in the San Gabriel Mountains above Pasadena in December 1903. He soon turned the conversation to astronomy and Hooker agreed to pay to bring a 10-inch telescope to California. Over the next decade and a half the Mt. Wilson Observatory would grow into the greatest observatory in the world.

A long-lasting friendship blossomed between the Hale and Hooker families. At the core was George Ellery Hale's fascination with Katharine Hooker and her close friend Alicia "Ellie" Mosgrove. This does not appear to have been romantic, as Katharine was almost twenty years older than the astronomer, but of a deep platonic and intellectual character. George Hale, Katharine, and Alicia spent a great deal of time together in the West Adams garden, mostly excluding John Hooker and Hale's wife Evelina. In 1906 Evelina was institutionalized with a nervous breakdown, and George Hale turned even more to the companionship of Katharine Hooker and Ellie Mosgrove at the house at 325 West Adams Street.

That year Hale asked John Hooker for his support for the 100 inch telescope he wanted for his observatory. In California historian Kevin Starr's account, John was "just barely" tolerated in the little circle of Hale, Katharine, and Alicia Mosgrove ("The Dream Endures: California Enters the 1940s"). John Hooker, hurt by his exclusion, sought entry into the circle by offering $45,000 to fund the Mt. Wilson telescope that was eventually named for him. This donation paid only for the casting and grinding of the giant mirror. The housing and observatory dome were to cost hundreds of thousands more, in part paid by the Carnegie Institute.

The reflector was to be 100 inches in diameter, the largest mirror telescope attempted up to that time. The disk for the telescope's mirror was cast in France and weighed four-and-a-half tons. Polishing it after it arrived took nine years. Apart from its giant mirror the Hooker telescope required a precision mount and clock drive, and a motorized dome. The fragile components were hauled up a primitive mountain road by mule and by trucks with mule teams harnessed on as auxiliary power. The site, so close to Los Angeles, might seem a bad choice, but the perennial inversion layer over the Los Angeles basin actually improved visibility from the overlooking mountaintop.

Early in 1909 an estrangement began between John Hooker and George Hale. This started with doubts about the quality of the glass lens cast in France, which had been delivered in Pasadena in December 1908. Hale's technical assistant, George Ritchey, a woodworker and self-taught astronomer, believed the glass was fatally flawed. This later proved to be untrue, but Hooker flew into a rage. He made common cause with Ritchey in castigating Hale for accepting the delivery.

But soon a hotter issue arose, in John Hooker's jealousy of Hale's friendship with Katharine, despite the fact that Hooker was seventy-one and Katharine already sixty. John's jealousy was general -- he came to prohibit any man to visit their Adams Street home when he was not present -- but he was particularly resentful of George Hale. This estrangement and Hale's continued deep regard for Katharine and her friend Ellie Mosgrove, were a major element in Hale's 1910 nervous breakdown. The breakdown caused Hale to flee to Europe for a prolonged recovery. His symptoms included seeing a little man who would appear in his rooms at night to offer sage advice.

John Hooker died in May 1911 with the rift still active. He never paid the last $10,000 installment of his $45,000 pledge for the telescope. The difference was made up by the Carnegie Institute; the telescope was given Hooker's name despite his default.

The telescope was completed and operational only in 1917, years after John Hooker's death. With this telescope in the 1920s, astronomer Edwin Hubble measured the distances and velocities of galaxies, work which led to today's concept of an expanding Universe. The Hooker remained the largest telescope in the world until 1948 when the 200 inch Mount Palomar Telescope was put into operation. In 1981 the Hooker Telescope was dedicated as an International Historical Mechanical Engineering Landmark.

Another figure important to the Hooker household was John Muir (1838-1914), America's most influential naturalist and conservationist, founder of the Sierra Club, and often called the "Father of our national parks." In the foreword to the collection of Muir's letters from his later years, "John Muir's Last Journey," Robert Michael Pyle writes of the period around 1910, "Muir returned four times to Los Angeles to lodge and write at the home of his wealthy friend John D. Hooker, the amateur astronomer and retired ironmaster. Muir's friendship with the Hooker family was vitally important to him during these years. Most of his best writing from this period was accomplished not in the 'scribble den' of the old Martinez ranch house, but in the garret of the Hooker's home on West Adams Street in Los Angeles, and many of his most expressive letters from the South America and Africa journey were written to J. D. Hooker's wife, Katharine, who was widowed several months before Muir sailed for the southern continents."

Muir remained close to John to the end. As he was preparing for his last voyage, at the age of seventy-three to the Amazon and then to the headwaters of the Nile in Africa, in August 1911 John Muir learned of John Hooker's death. Muir wrote to his daughter Helen, "I suppose you know that J.D. Hooker, the friend in our greatest need, was taken violently ill . . . and died Wednesday evening. . . . I wonder if leaves feel lonely when they see their neighbors falling."

John and Katharine had a son, Lawrence Hooker (1878-1894), who died of blood poisoning while attending Yale Law School in New Haven, Connecticut. Their daughter, Marian Osgood Hooker (1875-1968), became a physician and published numerous medical and scientific books. She was also a prominent amateur photographer. John Daggett Hooker is buried at Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery as is his son Lawrence and daughter Marian Osgood Hooker.

--compiled by Leslie Evans